Pain is a physiological and biochemical response to harmful stimuli and often indicates tissue damage. In cats, pain is processed through complex pathways involving both the nervous and immune systems. However, behavioral responses to pain in cats can differ from other species and are often subtle and difficult to detect. This is largely because cats, being both predators and prey in the wild, have evolved to hide signs of vulnerability such as pain.

In this article, we’ll examine the mechanisms of pain, how it is processed biologically in cats, and which behavioral cues might signal discomfort, helping you to better understand and protect your cat’s well-being.

While pain can be described in different ways, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines it as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.” The experience of pain starts with a process called nociception, which occurs in several stages:

•Transduction: When a harmful stimulus such as trauma, heat, or chemicals occurs, nerve endings called nociceptors in the skin, muscles, or organs are activated. These stimuli are then converted into chemical and electrical signals.

•Transmission: The signals generated by the nociceptors travel through peripheral nerves to the spinal cord and then to the brain.

•Modulation: At this point, the nervous system may either enhance or reduce the strength of the pain signals. Chemicals like endorphins play a role in modifying the sensation of pain.

•Perception: The brain interprets these signals as pain. This perception can vary depending on the individual’s previous experiences, emotional state, and level of attention.

Pain is generally divided into two main categories based on its duration:

Acute pain is a short-term type of pain usually caused by tissue injury from trauma, infection, sprains, dislocations, or arthritis. It serves a protective role, alerting the body to potential harm and helping to prevent further damage.

Chronic pain, on the other hand, lasts for three months or longer and may persist even after tissue healing is complete. It is often associated with changes in the nervous system and increased sensitivity. Chronic pain may not respond well to standard treatment and is often accompanied by symptoms such as depression. Most cases of pain are chronic, as acute pain, being sudden and short-lived, is less commonly observed.

To accurately understand, classify, and describe pain, several key terms are used in clinical and research settings:

Allodynia: Pain caused by a stimulus that wouldn’t normally be painful.

Analgesia: The absence of pain in response to a stimulus that would usually cause pain.

Anesthesia: A complete loss of sensation, including pain.

Hyperalgesia: An exaggerated pain response to a normally painful stimulus.

Hyperesthesia: Increased sensitivity to stimulation.

Hyperpathia: An abnormal, often increasing pain response to repeated stimuli.

Hypoalgesia: Reduced sensitivity to painful stimuli.

Hypoesthesia: Decreased sensitivity, especially to pressure or temperature.

Neuralgia: Sharp, recurring pain in the area served by a specific nerve.

Paresthesia: Tingling, prickling, or numbness that occurs without a clear cause.

Recognizing and understanding pain is essential for veterinarians and caregivers, as appropriate treatment depends on identifying pain accurately.

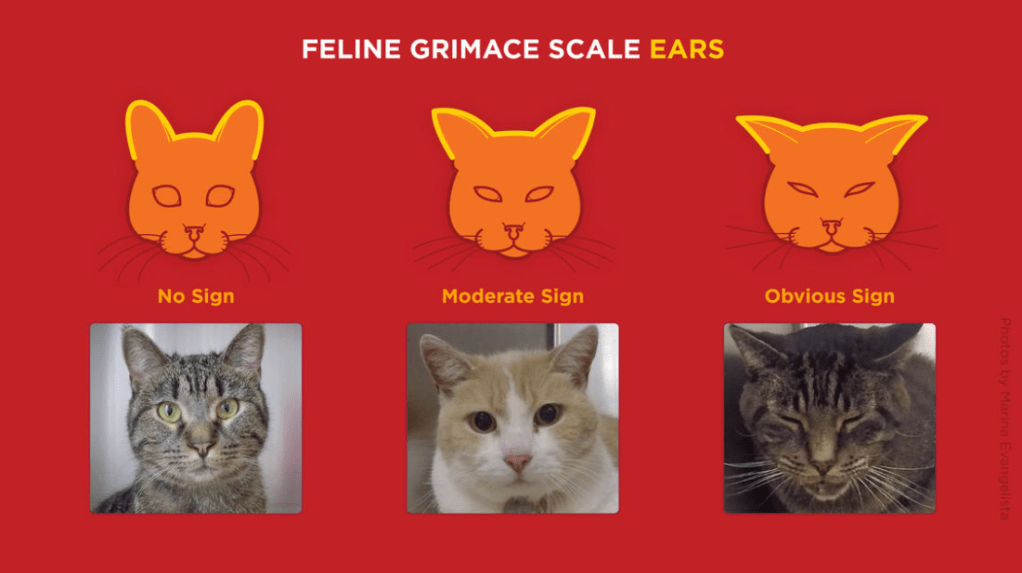

A recent study published in Scientific Reports introduced the Feline Grimace Scale, a tool developed to assess acute pain in cats based on facial expressions. This scale evaluates five key indicators: ear position, head position, whisker position, orbital tightening (whether the eyes are open or squinting), and tension around the mouth.

Dr. Daniel Pang from the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine emphasizes that these features reflect facial muscle tension, making them useful indicators of pain.

Beyond facial expressions, cats may show other signs of pain, including:

Behavioral Changes: Cats in pain may become less active, hide, or avoid social interaction. They may instinctively limit movement to reduce discomfort, which can provide clues about the pain’s location.

Posture and Movement Changes: Pain can alter a cat’s posture and how it moves. For example, a cat may hold its body in a specific way to protect a painful area.

Physical Indicators: Signs such as ears held back, squinting eyes, and facial muscle tension may indicate discomfort. Some cats may also excessively lick, bite, or scratch themselves (self-mutilation) in response to pain.

Vocalization: Unusual vocal sounds—such as excessive meowing, growling, or hissing—may signal that a cat is in pain.

If your cat is showing any of these behaviors, it’s a good idea to consult your veterinarian. Since pain can have various underlying causes, a proper diagnosis and treatment plan from your vet is the best way to ensure your pet’s comfort and health.

This blog post has been verified by Veterinarian Bedirhan AKYÜZ

Sources

Egger, C. M., Love, L., & Doherty, T. (Eds.). (2013). Pain management in veterinary practice. John Wiley & Sons.

Evangelista, M. C., Watanabe, R., Leung, V. S., Monteiro, B. P., O’Toole, E., Pang, D. S., & Steagall, P. V. (2019). Facial expressions of pain in cats: the development and validation of a Feline Grimace Scale. Scientific reports, 9(1), 19128. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-55693-8#citeas

Merola, I., & Mills, D. S. (2016). Behavioural signs of pain in cats: an expert consensus. PloS one, 11(2), e0150040.

Öngel, K. (2017). Ağrı tanımı ve sınıflaması. Klinik Tıp Aile Hekimliği, 9(1), 12-14.

Uluslararası Ağrı Araştırmaları Birliği internet sitesi. http://www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy erişim tarihi: 26.08.2024

Vedpathak, H. S., Tank, P. H., Karle, A. S., Mahida, H. K., Joshi, D. O., & Dhami, M. A. (2009). Pain Management in Veterinary Patients. Veterinary World, 2(9).

Website Resources

https://ucalgary.ca/news/cats-faces-reveal-their-hidden-pain