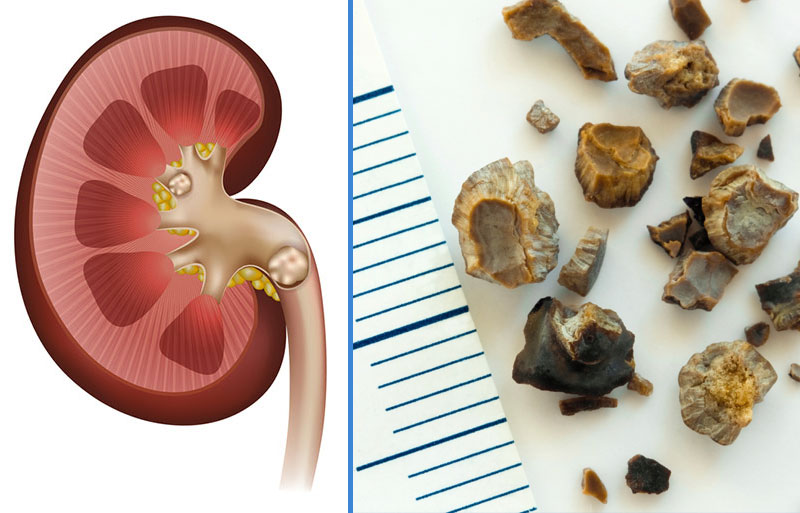

Urolithiasis is a disease characterized by the formation of urinary stones (uroliths) in the organs of the urinary system or along the urinary tract, influenced by species-specific predispositions. The term urolithiasis broadly refers to stones located anywhere within the urinary tract. These uroliths can form in the kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, or urethra.

The most common uroliths in cats and dogs are struvite and calcium oxalate. Uroliths composed of ammonium urate and cystine are less frequently observed.

Urine is a complex solution composed of dissolved substances. Some compounds tend to precipitate, while others increase solubility and actively inhibit crystallization. Under normal conditions, there is a balance between precipitants and inhibitors, and urine remains in a metastable state. However, excessive concentrations of precipitants or a deficiency of inhibitors can lead to the formation of crystals and uroliths. In some cases, urine pH directly affects the solubility of these compounds. Increased concentrations of urolith-forming components and prolonged transit time of existing crystals through the urinary tract predispose to stone formation. Additional contributing factors include urinary tract infections, diet, changes in urine pH, therapeutic agents, sex, and genetic predisposition.

Clinical Signs

In general, affected animals may present with pollakiuria, dysuria, painful urination, changes in urine color, urinary incontinence, anorexia, and lethargy. These signs vary depending on the location of the uroliths.

- Nephroliths: May cause sublumbar pain and hematuria, but clinical signs are often absent until the stones reach the ureter. Renal stones are typically left untreated unless ureteral obstruction occurs, with supportive care provided.

- Cystoliths: Can lead to hematuria, stranguria, and lower urinary tract inflammation. Some large stones may be palpated as thickening or friction along the bladder wall; however, the presence, number, size, and location of uroliths are usually determined by radiography or ultrasonography. The probable mineral composition can be estimated based on clinical data including age, breed, sex, urine pH, and urine bacterial culture. Definitive mineral composition is only determined through quantitative analysis of the stones.

- Ureteroliths: Acute or complete ureteral obstruction may present with vomiting, lethargy, and pain. Surgical intervention is required in cases of ureteral obstruction, as it is an emergency; untreated obstruction can cause hydronephrosis and irreversible kidney damage within days.

- Urethral Obstructions: May develop acutely or over several days to weeks. Affected animals often exhibit frequent attempts to urinate, inability to urinate, and vocalization due to pain. Complete obstruction causes uremia within 36–48 hours, followed by depression, anorexia, vomiting, dehydration, coma, and death within approximately 72 hours. Urethral obstruction is a medical emergency requiring immediate intervention.

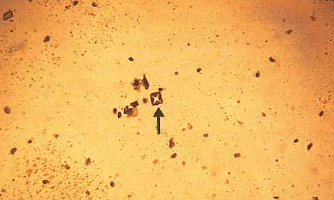

Struvite Uroliths

Struvite uroliths are most commonly seen in dogs aged 2–9 years and in cats aged 1–4 years or over 10 years. They are frequently observed in all cat breeds and in dog breeds such as Miniature Schnauzers, Miniature Poodles, and Cocker Spaniels. Struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) is the most common urolith in dogs. These stones are associated with urease-producing bacteria. Urea in the urine is broken down by urease into ammonium and bicarbonate. Ammonium combines with magnesium and phosphate, while bicarbonate raises urine pH. The pH change reduces the solubility of the ammonium magnesium phosphate complex, leading to the formation of struvite crystals and stones.

Due to anatomical differences, urease-associated infections are more common in female dogs than males. In dogs, struvite uroliths may dissolve over time, although there is a risk of urethral obstruction. In male dogs, the long narrow urethra and os penis region increase the risk of stone formation. In cats, sterile struvite uroliths can be dissolved using a diet restricted in magnesium, phosphorus, and protein while inducing aciduria.

Calcium Oxalate

In dogs, calcium oxalate uroliths are most commonly observed in individuals aged 5–12 years and in breeds such as Yorkshire Terriers, Miniature Poodles, Shih Tzus, and Bichon Frises. In cats, Burmese, Himalayan, and Persian breeds are predisposed to the formation of these stones.

The formation of calcium oxalate stones may result from excessive calcium or oxalate excretion or from a deficiency of urolith inhibitors. Although most cases are idiopathic, potential causes of hypercalciuria should be investigated.

In dogs, these uroliths are not dissolvable and must be removed surgically, via urohydropropulsion, or by lithotripsy. Cats with elevated ionized calcium require treatment tailored to any underlying condition.

Ammonium Urate

In dogs, ammonium urate uroliths are most commonly observed in individuals aged 1–5 years and in breeds such as Dalmatians, English Bulldogs, Shih Tzus, and Yorkshire Terriers.

A genetic predisposition has been demonstrated in Dalmatians, and a similar susceptibility is suspected in English Bulldogs. The formation of urate stones is associated with hepatic insufficiency, particularly with hepatic portal shunts. Liver dysfunction is linked to a reduced ability to convert ammonia to urea and uric acid to allantoin. Consequently, dogs with impaired hepatic function may develop hyperammoniuria and hyperuricosuria, which can lead to the formation of urate uroliths.

In cats, ammonium urate stones are generally idiopathic. Most urate uroliths occur in young cats and may develop secondary to liver disease or portal vascular anomalies. Efforts to dissolve these uroliths in dogs with liver disease should not be attempted.

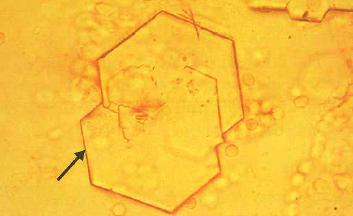

Cystine

In dogs, cystine uroliths are most commonly seen in individuals aged 1–7 years, particularly in the English Bulldog breed.

These uroliths are relatively rare. Although they can often be medically dissolved, they carry a risk of causing urethral obstruction. They are predominantly observed in male dogs.

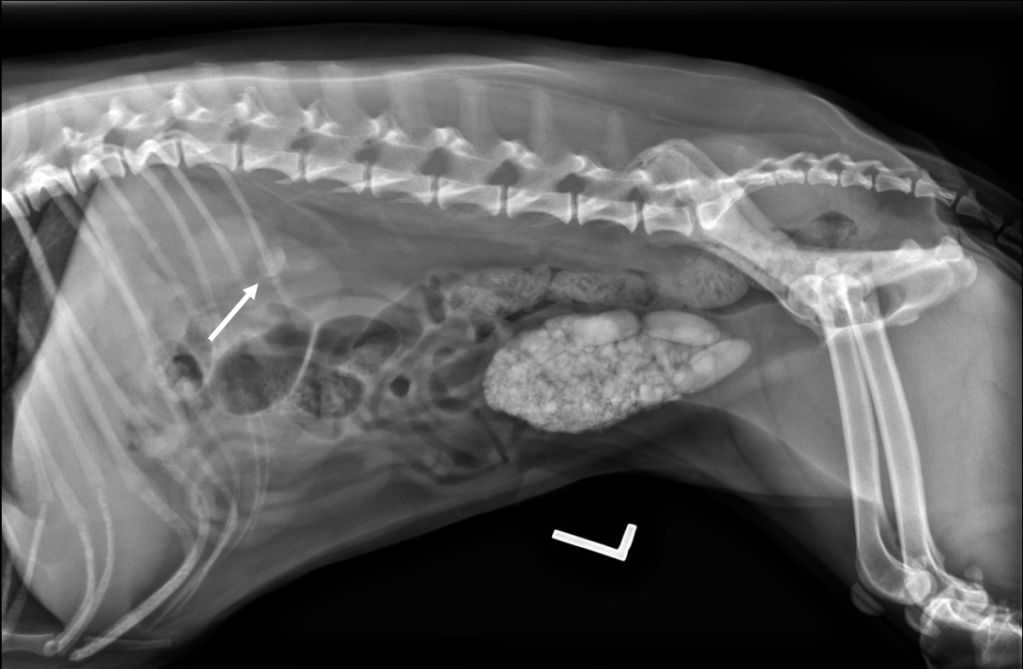

LL Radiography: Stone Formation Observed in the Urinary Bladder

All struvite, urate, and cystine uroliths are amenable to dissolution. In male patients, there is a high risk of urethral obstruction. Small stones can be removed with the help of a catheter. Additionally, phytotherapy is utilized as a complementary treatment in urolithiasis. The use of phytotherapy aims to improve the animal’s welfare. Furthermore, herbal urinary medications help control inflammation, increase diuresis, prevent crystal aggregation and potential growth, and facilitate excretion through the urethra.

Treatment Approach

After applying the necessary imaging techniques and examining the urine, the type of urolith is determined, and a treatment protocol is planned. This protocol depends not only on the location and chemical composition of the urolith but also on patient-specific factors. For example, the treatment plan may be tailored according to conditions accompanying urolithiasis, such as urinary tract infections or urethral ruptures.

In cases where medical management is insufficient, or when complete obstruction poses a life-threatening situation, the general approach involves removing the uroliths from the body using specific surgical techniques. However, it should be noted that the disease may recur in the future. Therefore, after surgery, recurrence risk can be minimized by maintaining urine pH within the normal range through appropriate medical and dietary support and by monitoring the patient at regular intervals.

This blog has been verified by Veterinarian Berk DEMİRER.

Resources

CLİNİCAL SMALL ANİMAL INTERNAL MEDİCİNE,UROLİTHİASİS İN SMALL ANİMALS, ALİCE DEFARGES DVM, DACVIM (SAIM), MİCHELLE EVASON DVM, DACVIM (SAIM), MARİLYN DUNN DVM, DACVIM (SAIM), ALLYSON BERENT DVM, DACVIM (SAIM) BOOK EDİTOR(S):DAVİD S. BRUYETTE DVM, DACVIM (SAIM), NİCK BEXFİELD BVETMED, PHD, DSAM, DİPECVIM-CA, PGDİPMEDSCİ, PGCHE, FHEA, MRCVS, JOHNNY D. CHRETİN DVM, DACVIM (O), LİNDA KİDD DVM, PHD, DACVIM (SAIM), STEPHANİE KUBE DVM, DACVIM (N), CATHERİNE LANGSTON DVM, DACVIM (SAIM), TİNA JO OWEN DVM, DACVS, MARK A. OYAMA DVM, MSCE, DACVIM-CARDİOLOGY, NATHAN PETERSON DVM, DACVECC, LİSA V. REİTER DVM, DACVD, ELİZABETH A. ROZANSKİ DVM, DACVIM (SAIM), DACVECC, CRAİG RUAUX BVSC (HONS), PHD, MACVSC, DACVIM (SAIM), SHEİLA M.F. TORRES DVM, MS, PHD, 30 APRİL 2020, HTTPS://ONLİNELİBRARY.WİLEY.COM/AUTHORED-BY/DEFARGES/ALİCE, Date of use: 13 HAZİRAN 2024

Schaer M., Gaschen F., 2019. Köpek ve Kedilerin Klinik Hekimliği. Tekirdağ, TR: Nuri Altuğ. 493-501 syf.

ROCHA, CO.; GRANATO, AC Köpeklerde ürolitiazisin fitoterapötik tedavisinde kullanılan şifalı bitkiler – bütünleştirici bir incelemede. Araştırma, Toplum ve Kalkınma , [S. l.] , v. 10, hayır. 12, s. e501101220876, 2021. DOI: 10.33448/rsd-v10i12.20876. Şu adresten ulaşılabilir: https://rsdjournal.org/index.php/rsd/article/view/20876. Date of Use: 14.02. 2024.

Yorum bırakın